Disrupting Automation: Capitalism, Technology and the Post-work Society

This is an extended version of the talk “Disrupting Technological Change”, delivered on October 2017 at the annual conference of the Institute for Labor Studies in Ljubljana.

Machinery … enters not in order to replace labour power where this is lacking, but rather in order to reduce massively available labour power to its necessary measure. Machinery enters only where labour capacity is on hand in masses. - Karl Marx, Grundrisse

Technological unemployment and political instability

Automation and technological unemployment are a recurrent phenomenon and a recurrent feature of public debate in advanced capitalism. The talk of the end-of-work, or in its modern-day variant of the post-work, has been with us at least since the publication Jeremy Rifkin’s eponymous book in 1995, if not since the 1970s and the beginning of the great neo-liberal shakeup. This is not unjustified. In macroeconomics, the employment growth is commonly calculated as a differential between the output growth and the productivity growth. This fundamental identity implies that for as long as the output growth outpaces the productivity growth, not all productivity-enhancing technology will necessarily lead to unemployment. However, since 1950s the world economy’s output has been decelerating and in 1970s it was outpaced by gains in productivity. As output growth rates have gone down and productivity rates have gone up, the unemployment has expanded. Capitalism does need less labor today.

The reason for this is that over the last couple of decades the technological change has made large segments of the industrial workforce along with its qualifications redundant. According to a survey conducted under Barack Obama’s administration, in the U.S. the participation rate of economically active men in the age group 25 to 54 has gone down over the last half of century from 98% to 88% - primarily because of technological change (but also record levels of incarceration of prime-age African American men who are slaving away in the U.S. American prison-industrial complex).1 Immediately after Donald Trump’s electoral victory - a number of leading labor economists went on record stating that a majority of lost jobs cannot be brought back - again primarily because of technological change. While some 2.4 million U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost to China, another 5 million were lost to automation. In 1970s General Motors produced fewer vehicles than today with three times as many worker.2 Walmart as the world’s largest private employer has over 2.6 million workers, whereas its prospective contender Amazon.com only 350,000. Judging by the current growth, if and once Amazon.com’s revenue reaches Walmart’s, it will require a million and a half workers less.

This parallel and combined restructuring of the labor market through the global division of labor and the technological change is becoming a major cause of political instability in capitalist democracies. As recent political shakeups have shown, the working class in advanced economies, mostly white middle-aged men and their families that can still recall the period of “good jobs” that once were the backbone of the national economy, have now become a fulcrum of political strategies directed against the political establishment. The new conservative nationalists in the core countries of Western capitalism - the U.S., U.K., France and Germany - are seeking their legitimating flywheel in the social discontent of that part of the electorate. The neo-liberal governmentality has done away with any notion that the democratic participation of the popular masses may exert the impact on imperatives of globally-integrated economic processes and protect them from the deleterious effects of the economical restructuring. Voter turnout and duopoly of the center are therefore in decline. In response, the new far right is seeking to embody contradictory interests by promising, on the one hand, strong protectionism, border walls and return of old industries, while on the other hand leaving intact the agenda of the radical center - deregulated global markets.

Yet these political troubles might turn out to be trivial to what awaits us in the future. If we are to believe the cautioning warnings, the loss of full employment and jobs in the previous decades - mostly hidden in the employment statistics under various forms of underemployment - are nothing compared to what seems to be lying in the wings of the decades ahead of us. In their oft-referenced study on the future of employment from 2013 the Oxford Martin School researchers Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne have analyzed the technological replaceability of jobs in the U.S. labor market and have concluded that no less than 47% of all jobs fall into the category of high risk of replacement.3 Such a drastic figure that Frey and Osborne arrive at is based on their novel approach to analyzing replaceability - they don’t assume technologies that are already in use, but rather technologies that are scheduled to become generalized throughout the economy in the coming decades. The technological mix that accounts for this drastic shift is made specifically of big data, artificial intelligence and mobile robotics. The exponential advances in computing capacity and massive deployment of sensing technologies have created prerequisites for the artificial intelligence to be able to discern patterns in a mass of data, dynamically learn and autonomously adapt to changing conditions. This transforms non-routine tasks, which were until recently considered impossible to replace, into “clearly defined problems.”4 These technologies can then also be deployed to control a new generation of robots that is far more successful at completing tasks that require physical dexterity, precision and adaptation to context.

Technologies in the capitalist mode of production

Before further analyzing the technological unemployment and the prospects of a post-work society, a brief Marxian account of the structural relation of technological development and capitalism is in order.

To start with, not every development and deployment of technological innovation is driven by the imperatives of accumulation of capital. For instance, during the first decades of its existence, the Internet carried the promise of a radical democratization of mass media, autonomy of communication infrastructure and expansion of cooperative production. In certain libertarian visions also the realization of the ideal of competitive markets without monopolistic concentration of economic power. However, by mid 1990s the Internet became a focus of an intense process of commercialization, commodification and monopolization. Online advertising and electronic commerce became the economic foundation for the development of communication infrastructure, applications and content. Concomitantly, digital networks became generalized allowing for integration, optimization and coordination of global supply chains, while computer technologies were massively used to expand financial instruments and markets. The capitalism has thus only gradually commercialized the Internet and transformed it into a technology that became generalized across other sectors of the economy.

However, a large part of the development and deployment of technological innovation does unfold under the imperatives of accumulation of capital. Starting with its agrarian origins, the advance of capitalism was accompanied by an accelerated development in production, transportation and communication technologies, primarily based on the discovery of fossil fuels. Capitalist mode of production not only uses technologies, but in its own development it starts to transform these processes into advanced techno-scientific processes where the “automatic system of machinery” becomes “the most adequate form of capital as such”, one that subsumes all living labor to its own internal organization and dominates it as an autonomous force.5 In the form of a generalized techno-science, which is nothing but the objectified working knowledge produced by living labor in its collective form, that which Marx of The Grundrisse calls “general intellect”, the technological development becomes a separate system that transcends the level of any individual working knowledge, individual production process and individual capital. Advance capitalism’s tendency, one in which the state plays an important regulatory role, is to subordinate and integrate that techno-scientific system to the imperatives of accumulation of capital. As Harry Braverman notes in his Labor and Monopoloy Capital “key innovation is not to be found in… any of the products of these science-technologies, but rather in thetransformation of science itself into capital.”6

Against the backdrop of this techno-developmentalist tendency, the role of technologies can also be understood form the inherent dynamics of the capitalist mode of production. The surplus value under capitalism is produced by the surplus labor over and above the necessary labor needed to recoup the cost of worker’s wage. By reducing the relative duration of labor time spent on recouping the wage the capital increases the relative proportion of surplus labor from which it accrues surplus value and profit. That relative proportion can be increased either by extending the total working hours, generating thus in Marxian terms absolute surplus value, or by increasing the productivity of labor and thus reducing the time needed to recoup the wage, generating relative surplus value. The relative surplus value grows as the productivity of labor grows - an effect that can be achieved either by improving the organization of or the introduction of new technologies into the production process. The increased productivity not only reduces the necessary time needed to recoup the wage, but also at the level of aggregate economic totality reduces the cost of commodities that regulate the cost of labor. As Marx notes: “The increase of the productive force of labour and the greatest possible negation of necessary labour is the necessary tendency of capital, as we have seen. The transformation of the means of labour into machinery is the realization of this tendency.”7

However, capitalism is also a system of generalized competition. Individual capitals competing with each other in the marketplace are constantly driven to increase the productivity of their labor in order to better the competition - either by increasing the surplus value in their product, offering their product at a lower price or shifting the market altogether. This pushes capitalist companies to innovate. As the tendency is that a productivity-enhancing innovation quickly gets generalized across an entire sector, over time companies are forced to invest more and more into technological innovation and replacement of the existing technology with a new one. Thus, in the composition of their capital, they increase the relative proportion of means of production, while they reduce the relative proportion of labor. Given that the labor is a source of surplus value, growing investments into technologies lead to general erosion of profit across the entire sector. This, in turn, leads to the crisis of overproduction, where there is not enough demand for increased output of products, and the crisis of overaccumulation, where investment in production becomes no longer profitable. In periods of such crises, instead of investing in no-longer-profitable production, capital turns to financial markets, where speculative bubbles provide means of maintaining profits, and too risky innovations that might eventually shake up entire markets. This cyclical development can also be observed in the recent Great Recession that was ushered by a sudden development of Internet technologies a decade earlier, ensuing dot-com bust, increased investment into secondary exploitation in the real-estate market, overheating of financial markets and finally the private debt crisis. The resolution to this crisis is now either being sought in the accelerated innovation in automation that should restore production to profitability or in the enormous investment runs on financial technologies such as cryptocurrencies. So far both strategies have primarily a speculative character.

Finally, one should also note that the aggregate technological base of the present day society is dependent on the intensity of economic processes, on the intensity of investments into technologies, on the intensity of matter and energy throughput that are altogether characteristic of advanced capitalism. The technological base is not sustainable without that intensity of the global capitalist system, just as the integration and coordination of the division of labor in the global capitalist system are not sustainable without such technological base.

Technological development is possible outside of capitalist relations. In capitalism’s focus on competition and quick profit, social needs are not at the center of technological development. Absolved of the profit-imperative, the existing technological base could provide both a much fuller and equitable fulfillment of social needs, and a more meaningful development of technologies. To the degree that capitalism is a catalyst of technological development, it is also its limitation.

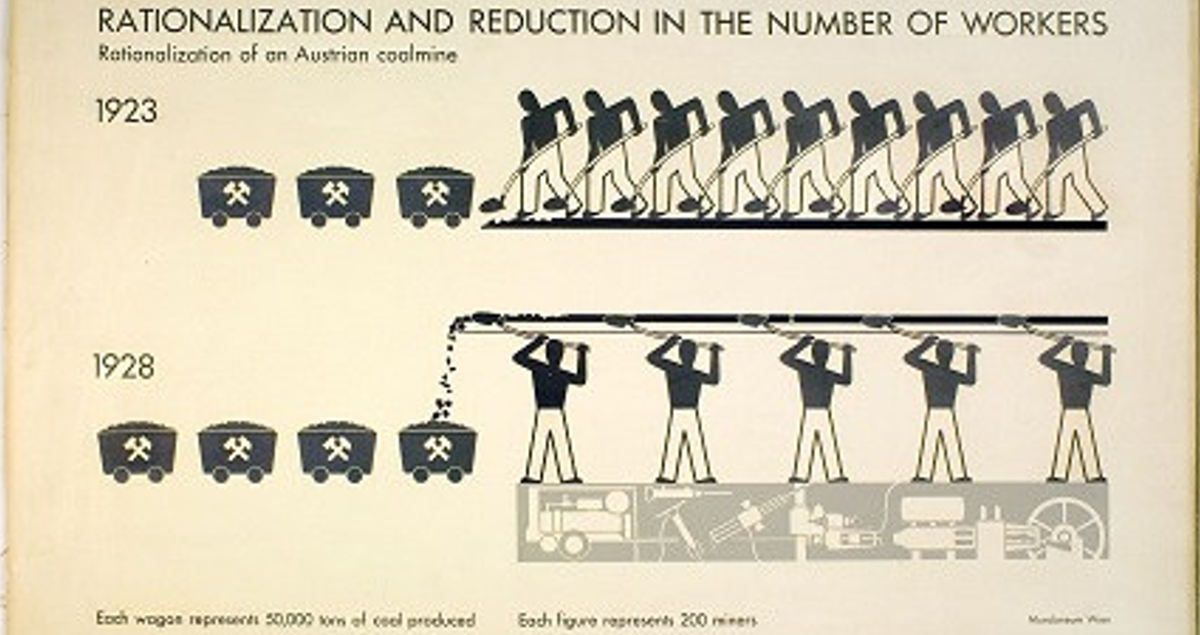

The long history of labor-substituting innovation

Over the next two sections, I’ll look at the history of productivity-enhancing and labor-substituting innovation in order to indicate that the fatalist accounts of the coming automation with their anticipation of mass unemployment obfuscate the aggregate substance of technological development under capitalism: re-structuring of capital-labor relation. The economic tendency of this process is an increase in the quality and speed of production, efficiency of labor and productivity of capital. Yet its social tendency is an increase in the control over production process by the owners of capital, constant restructuring of the labor market and curtailing of labor’s organized resistance to the conditions imposed on it by the dynamics of capitalist accumulation. However, that socially antagonistic character of technological development is black-boxed in the prevailing dogma that innovation is spontaneous, inevitable and best left to the invisible hand of the market. If we want to maintain a transformational attitude toward capitalism, we need to maintain a confrontational attitude toward technologies.

In capitalist societies the labor market is the fundamental mechanism of social integration. Thus, the majority of the population must find work in order to secure for themselves and their family food on the table and roof over the head. In developed consumer societies one or two items more. So, they are willing to work more under worse conditions for a lower wage. The expansion of atypical work over the last decades in advanced economies - not dissimilar to the prevailing condition elsewhere - attests to that. It is against the backdrop of this fundamental given of capitalist societies that the technological development rears its class characters: by increasing the unemployment and growing the reserve army of labor it drives down wages and disciplines the labor force.

So, let me revisit the history that the reader will probably be more than familiar with. Automation, robotization, computerization - in short, introduction into the process of production of machines that can execute tasks without direct human labor or supervision - come at the tail end of a long history of innovations in the organization and technology of production that span from the early days of manufacture to the fully automated global supply chain of today.

As the canonical 18th century account of the pin factory provided by Adam Smith already had it, the analysis of work tasks, their segmentation into yet smaller tasks, standardization and narrowing-down of working knowledge and skills are the prerequisite for substituting workers - be that with lower-skilled labor or cheaper technologies.8 However, the introduction of new technologies creates demand for a skilled labor force that can innovate and operate it. This new skilled labor is again a burden to profits and thus leads to further innovation in routinizing work tasks and substitution of those workers by machines.

The era of industrial capitalism started with the technical division of labor into individual tasks. With the simplification of work tasks the craftsmen - who hitherto maintained the control over the production by means of their professional skills and the control over the labor market by means of their professional guilds - became replaceable by unskilled workers. Although this unleashed a huge growth in jobs, a democratization of manufacturing labor of sorts, the effects of new organization and new technologies of production in the period of first and second industrial revolution were frequently a cause for worker discontent. Horrific labor conditions and brutal competition imposed on the workers resulted in the first collective struggles for workers’ rights that took, amongst others, the form of organized smashing of the machines.

The second major transformation started with the introduction of scientific management. Scientific management breaks down workplace tasks into individual actions and analyses them in terms of time and motion needed for their execution. A production process that has been broken down on Taylorist principles can then be re-composed so as to increase efficiency and impose on the worker the accelerated pace of machine-driven production. By reducing the control of laborer over his/her own actions this paves the way for the Fordist organization of the integrated factory system based on continuous flow manufacture on production lines, in turn giving rise to a new caste of technical professions in charge of design and maintenance of a technological system. Slowly the innovation process stops being driven by inventions stemming from the production process and is separated out into a system of techno-science organized around R&D departments and universities. What workers have lost in terms of control over the production process, in the large factory systems they have received in the capacity to mass organize, to obstruct the production and claim their rights.

After the WWII ensued the third major transformation: with the introduction of automation (curiously enough that term was coined in 1948 by a Ford Motor Co. executive) the skilled workers lost the last bit of control over the machine. They themselves became mere attendants to the machine, while their professional skills were made redundant. However, due to the post-war economic expansion and the strength of the unionized labor, the majority of the workforce could find new jobs. The effect of automation was delayed. It was only with the advances in cybernetics and microelectronics in the 1970s and 1980s that the advanced industrial robots started to enter shop floors and that substantial replacement effects would become felt once the economic crisis died down. In parallel, business computers massively entered the top floors reducing the need for a number of clerical jobs. Computers and networks made possible the generalization of the just-in-time organization of production and the global supply chains that connect manufacture, logistics and marketing into real-time feedback loops. The technology has enabled global division and arbitrage of labor. This moment coincided with the transition to the neo-liberal regime of accumulation, where the monetarist policies, cutting down inflation and raising interest rates, had unleashed a process of restructuring and closing-down of low-profit factories, mass lay-offs and relocation of manufacture to lower-wage countries.

This has lead to a polarization in the labor markets of advanced economies between a massively growing low-skilled workforce in the service sector and a high-skilled workforce commanding the production. As analysts such as Tessa Morris-Suzuki noted already in the early 1980s, this polarization was driven by a shift in the primary site of surplus value creation: it drifted from production to innovation, accompanied by a thorough reorganization of the techno-scientific process and rise of the knowledge economy.9 Today this historic processes is continuing with a new round of robotization and computerization that is threatening to do away with the occupations where human labor was until recently considered indispensable, such as transport, retail, construction, or even some high-skilled occupations such as paralegals.

If we view the history of automation from the 1970s onward, first it was the routine manual jobs that were lost, then the routine cognitive jobs, and now it is non-routine jobs requiring motor skills and problem solving that will be lost. While the early industrial era technologies were de-skilling technologies benefiting low-skilled labor, the technologies in the 20th century had required a constant race in raising skill levels. Over the last couple of decades, the massive adoption of ICTs has substantially contributed to a polarization of the labor market into highly paid high-skilled professions and low-paid low-skilled professions. Today only professions requiring creativity and social intelligence have remained irreplaceable.

Class-dynamics of technological change

Advanced economies have seen enormous gains in productivity and wealth over the last decades, yet this growth did not accommodate the needs of the broad segments of population, but rather has led to creeping underemployment, precarity and social polarization.

Why didn’t the enormous gains in productivity result in a post-work society? A partial reason can obviously be found in the fact that production is not driven by the satisfaction of social needs, but rather by the expansion of surplus and profit that are privately appropriated and steered toward the reproduction of capital. Yet a more curious question is why haven’t these enormous gains in productivity result in equally large levels of unemployment? Many advanced economies have after all seen a drop of labor force in manufacturing over the last decades. But only a small rise in unemployment. Why is that? Well the reason is that the replacement of workers by machines increases the reserve army of labor and thus reduces the cost of labor. Such labor can be then cheaply employed in the next cycle of expansion of commodity production. At the same time, the gains in productivity lower the price of commodities and thus leave a disposable income that can be used to buy new commodities in these new markets.

It is this mechanism that has allowed the industrial workforce to become a reserve army for the expansion of the low-waged service sector in the 1970s. Service sector boom was based on the intensive commodification of a number of needs related to social reproduction that before used to be mostly fulfilled outside of the market, such as recreation, cooking, health or entertainment. Based on such dynamics the mainstream economics treats technological unemployment as a temporary phenomenon that finds its resolution in technologically-driven productivity growth, leading to economic expansion and finally restored employment growth. The workforce made redundant in the process must either acquire new skills or drop out of the labor market altogether.

However, while over the last decades the technological change has had only modest effects on employment rates, it has disproportionately benefited the higher-skilled labor and the capital. Eight men own together more than the poorer half of the humanity. Five of them are from the information technology sector.10

This begs the question: to what degree does the general direction of technological development condition social asymmetries and is this direction necessary? What is its exuberant rationality that generates such spectacular economic inequalities, while it could provide welfare for most of the humanity? Considering the historic process of productivity-enhancing innovation I have described earlier, it is clear that its social substance is a constant reorganization of production for the purposes ever-intensive capital accumulation, the process Marx has called the real subsumption. However, this general tendency is fought ought as a constant antagonism between labor and capital over the concrete organization of production process and allocation of resources for social reproduction. This is where abstract universal of capitalist development and concrete particular of its overcoming meet.

In his seminal study Forces of Production, focusing on the post-WWII automation in the U.S., David Noble takes his cue from the statement made by Charles E. Wilson, the president of General Motors and the Secretary of Defense in 1950s, who warned of the two great problems the U.S. was facing in those early days of Cold War: “Russia abroad, labor at home.”11 The immediate context of that statement was the fact that the WWII and immediate post-war period, despite the conditions of a war economy, was marked by an unprecedented labor militancy and intensity of strikes that had resulted in substantial gains in wages and concessions in labor rights. Analyzing the early automation in those sectors that had participated in the war industry, primarily machine engineering, Noble comes to a conclusion that the priorities for the military-industrial complex was first to neutralize the trade unions by drumming up the Red Scare and then to reduce the control of labor over the process of production through introduction of automation.

A closed feedback loop between a machine and a program should have excluded the machinist from controlling the production of a part, whose specification and speed of production was now transferred into the hands of engineers and management. The worker who only attends to the machine can easily be replaced. The worker that can be replaced doesn’t strike. Tellingly, the exclusion of the worker as a controlling instance led at first to numerous product faults and machine malfunctions, i.e. substantial losses in productivity. Nonetheless, the automation was carried through as the imperative for the management was to regain the control over the process of production and reduce the claim-making capacity of the workforce. Thus the automation is revealed as a direct means of class struggle.

Obstacles to technological change

Judging by the U.S. employment statistics, technological change in the aftermath of the recent Great Recession will have substantive effects on the labor market. The crisis was a trigger to lay-off relatively costly workforce and ever-cheaper robots are an incentive not to bring it back. Productivity and output after 2008 were restored much sooner than employment.

And yet, the potential of new labor-substituting technologies is not a foregone conclusion. We know that historically the deployment of technological innovations was not a linear process, but was rather shaped by numerous adaptations, resistances and failures. In fact, the deployment of new labor-substituting technologies can stumble over three sets of obstacles.

The first is related to the introduction of a new technology into the process of production, where it has to undergo a number of adaptations to the extant machinery and organization of production. This process can frequently result not in the replacement of labor, but in additional labor needed in resolving interoperability, optimization and monitoring issues of the new equipment.

The second is related to socio-economic factors: the social cost of unemployment or drop in the value of human capital due to technological change can lead to a resistance of the labor, unions and political institutions in an attempt to defend the existing employment. The path dependency due to technological choices made in the past can also lead to an inertia and to struggle for market power by non-competitive means, stifling innovation. Externalities such as ecological impact can lead to resistance by activists and regulatory intervention.

As the economic historian Joel Mokyr points out, history teaches us that if technological change is not accompanied by redistribution from winners to losers, the innovation will face major push-back in its deployment.12 In the neo-liberal era of retrenchment, the winners can thus count on growing social resistance and it is our responsibility to provide it.

The third is related to the structural dynamics of capitalism: namely, if automation is driving down the price of labor, it lowers the economic motivation to replace workers with machines, thus slowing down the entire process of replacement. This is particularly the case in labor-intensive and technologically stagnant sectors where profits are low and don’t allow for reserve capital to be accumulated to make investments in new equipment - such is the case of a large segment of the service sector oriented toward end consumers, the sub-sector that employs a great deal of global workforce.

Here the replacement is possible by creating an economy of scales - by mergers and crowding out of small competitors - such is the case currently with Amazon.com and street retail. However, not everywhere is the economy of scales possible, as service sector is highly fragmented into small enterprises and freelancers, tied to location, social context and human interaction, thus requiring too big capital investments in technologies for very limited returns. Human work of care, domestic work and social reproduction is insistently proving resistant to robotization, as perceived “lack of care” can have detrimental effects on the wellbeing of care receivers.13 Technological changes in this segment of the labor market will be more directed toward the on-demand contracting of atypical jobs such as provided by various online gig-economy platforms - e.g. Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk, Uber or Upwork - that will ultimately lead to further casualization of labor conditions and competitive pressures on wages.

Furthermore, investments in capital goods, growth rates and profit rates of global capitalism are at a low point. For instance, investments of the manufacturing sector into the information technologies, despite the promises of the fourth industrial revolution, are at lower levels than they were at the height of the dot-com boom at the end of the 1990s.14 As the Solow paradox states, the contribution of IT to the productivity of manufacturing sectors other than IT is nowhere to be seen in statistics of economic performance.

Given that labor is productive of surplus value, further reduction in labor and increase in technology would only lead to a further erosion of profits. All this suggests a conclusion that capital is not likely to be suddenly overcome by an irrational desire to invest in highly unprofitable sectors that employ the bulk of the workforce. In the developmental trajectory of the present-day crisis capitalism, the expected speed and scope of replacement of labor by machines thus seems somewhat improbable.

As a study published in early 2017 by McKinsey Global Institute warns, the replaceability analysis still does not take into account the complexity of replacement in occupational situations where occupations still include a large number of non-automatable tasks. If this complexity is taken into account, it is as low as 5% of occupations that can become fully automated, while the process of automation might drag out decades into the future. 15 So, the situation might not turn out as drastic as predicted by Osborne and Frey.

Thus betting on radical unemployment to transform our economy into a post-work economy on its own is premised on weak assumptions. Nonetheless, our technological base, its capacity to relieve us of a great deal of work, currently limited by capital-labor dynamics and exigencies of capital accumulation, does provide an opening for politics and an opening for technopolitics - if a post-work society cannot be achieved on its own, it nonetheless doesn’t mean we cannot work to achieve it.

Disrupting technological change

Spearheading the computerization process that forms the basis for alarmist predictions of technological unemployment are giants that dominate the global digital economy. This is where the action is. They are trying to capitalize on the fact that they already command large computing capacity, big data and engineering know-how by complementing it with intensive investments and acquisitions in the field of robotics and artificial intelligence. For example, Google has been for years at the forefront of autonomous car development, in 2013 it acquired military-oriented Boston Dynamics, while in 2015 it acquired the leading AI company DeepMind. In 2012 Amazon.com bought Kiva Systems in order to automatize its fulfillment centers, while in 2017 it opened a fully automatized grocery store. Facebook, Apple, Intel and IBM are no laggards in the efforts to divvy up the future industrial automation market either. These are mostly global monopolists who hold enormous reserve capital resulting from their fantastic financial market valuations and even more fantastic tax evasion schemes to reposition themselves as the technological infrastructure purveyors for the future automation in other sectors: manufacture, health-care, logistics, military or finance.

This capital-intensive race has three major consequences on understanding what might the coming automation look like. First, the next wave of automation will likely not be a revolution in microproduction where even the smallest of producers will have their own autonomous robot, but rather the automation will be concentrated in the hands and developmental logic of a small number of big corporations. Second, to most it will become available as an off-site service they’ll be able to buy from these corporations. Economies of scale and network effects are important here. Third, as efforts of European Union to protect privacy or enforce taxes indicate, the operation of global corporations headquartered in the U.S. or elsewhere will be hard to regulate.

For the new generations, the structural unemployment will shape out differently than for the generation that lived through the transition from a standard model of full employment to a flexibilized employment. It will not express itself as a localized dismantling of manufacturing jobs. As the recent research by the labor scholar Ursula Huws indicates, the confluence of three trends - a jobless recovery, a growing precarious informal tertiary and creative sector and the rise of online platforms transacting atypical work opportunities such as Mechanical Turk or Upwork - it will primarily the form of increased global labor market competition where it will become harder and harder to secure ever smaller number of jobs.16 The strategy of finding a job will be accepting lower wages or “entreprecariat”17 that will demand a constant adaptation of workers to the changing demand and subjection to the despotism of the consumers. In the countries of capitalist periphery, where the extant technological base is low in productivity and investments in technology sparse, the accelerated technological advancement and increased productivity in the core economies of capitalism will lead to a further lagging-behind and downward pressure on the price of labor, deepening labor insecurity and impoverishment for those who are not able to be fast enough in acquiring new skills in high-skill professions such as software developement or design. Finally, the increased unemployment in the core economies could reduce legal opportunities and illegal conduits for labor migration.

There are several strategies that regulators will be forced to try in this transition - in order to secure greater competitiveness of workforce and social stability at home: first, increase the baseline social security (for instance introduce basic, but not universal basic income) for those who are underemployed in permanent atypical work conditions; second, intensify the free educational opportunities that develop the work skills but more importantly the least-replaceable creative capacities; third, increasing the bargaining power of fragmented labor force; fourth, democratize the access to the means of production. Failing that, they’ll face a potential disintegration of that fundamental mechanism of social integration - participation in the labor market. In addition, they’ll face the erosion of purchasing power of a large base of consumers and the problem of a collapsing demand.

However, what ultimately matters is whether we will be able to politically push through a post-work society. Part of that challenge is whether we will be able to wrestle the technological development away from the “natural” forces of the market and return it into the hands of societal steering. This is what organized labor has managed to partly prevent in the earlier cycles of labor substitution. This is what engineers have tried to do when they placed themselves at the service of the labor, as Norbert Wiener who placed himself at the service of United Automobile Workers in the late 1940s to counter the threat of automation.18 Likewise, this is what the left block in the European Parliament has attempted with a proposal to tax robots, a proposal that was neither too early nor unjustified - but rather too modest and disconnected from other social forces.19

Orientation of technological development is largely overdetermined by social antagonisms - and political opposition to technological development, that can proudly don the name of Luddism, makes the antagonisms explicit. Transformation starts with negation. It is clear to many that we need to change the societal patterns of production and wealth redistribution so as to minimize the dependency on employment and uncertainty from disruptive technological change - and secure the environmental transition to a more sustainable social metabolism globally. Active intervention into and opposition to technological development - in the development, at the place of work and in everyday, or in the political arena - is key to its social re-orientation. If the technological change can disrupt the society, the society can certainly disrupt the technological change.