Disability, Discrimination and Desire not to Be

A reflection in response to the harrowing video of Quaden Bayles, a nine year old aboriginal boy with achondroplasia dwarfism, who has been repeatedly subject to bullying at school and wants to kill himself.

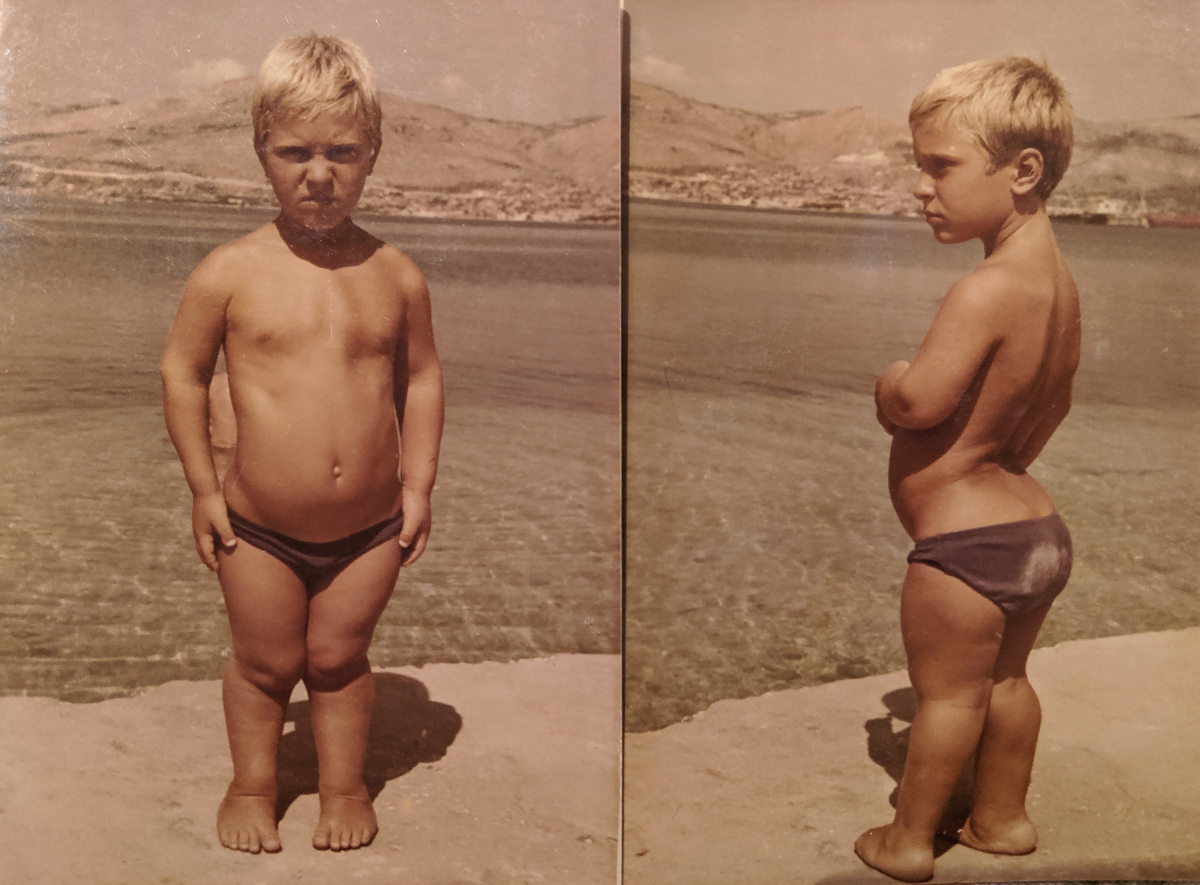

It’s pseudo achondroplasia dwarfism in my case. I can’t recall ever being bullied in school on account of my dwarfism (or for any other reason). I always had one or more designate classmates to help me out, classes were organised in accessible classrooms, and schools did their best to accommodate my impairments in many different ways, ways that in some respects seem unthinkable today – most radically the socialist social and disability security system provided dedicated private transport to take me to school and back (luxury communism, eh?). A lot was done to socialise my condition both institutionally and among my peers.

However, with all the extraordinary support and accommodations, I still could not avoid feeling different. In many activities kids were expected to be agile to fulfil this or that expectation, to accomplish this and that, to venture into this or that, to discover this or that. Kids would notice the difference and ask their parents who would be too embarrassed to explain. More generally teachers and parents did not address and affirm differences across a whole range of (in)abilities, particularities and backgrounds that kids come with – in a way that would explain to kids that we are all different in more than one way and that differences make us singular beings that we are. All these factors converged to suggest that only some kids are different. As a kid – and you might not be outright disabled but only not able enough – you learn to internalise that suggestion very quickly, so much so that you come to resent your own difference, pitty yourself, wish you were not what you are and, as in the case of Quaden Bayles, wish yourself not be.

Paradoxically, you learn to reproduce that very mechanism by othering others who are different in this or that way. As a disabled kid you start not only to resent your disability but see other kids’ differences as worthy of othering and avoidance. A discriminated person is not necessarily an ally of another discriminated person. The failure to address differences can play itself out in consequential ways. For instance, I was always told that what matters is the brains and not the legs, a compensatory argument that negates not only emobodied aspects of existence but also legitimates school’s bias against those who struggle with learning. In the context of my school, this more often than not included Roma kids. A chain of silences thus reproduces exclusions that define the lives of kids going forward.

The internalised feeling of inadequacy only grew stronger as I returned from the USSR less mobile as a consequence of series of surgeries and adolescence kicked in with its different patterns of socialisation. These patterns were no longer centered at home nor at school, neither at play nor at learning, and thus as the registers of social experience of my peers expanded, I could only think of my social world as increasingly limited. I transformed this inability to access a big part of the social world of my peers, including romantic relationships and sexuality, into a sense of my own abjecthood. In retrospect, almost the whole decade from when I was 11 to when I was around 20 is a decade I’d rather not return to. Obviously many adolescents struggle to find their bearings, but disability can easily add a sense of inescapable stigma. I would only emerge from this difficult period when I started to socialise more at the university. Now, as I have entered my middle age, I no longer feel inadequate or abject, just different. Limited mobility and built environment are always there as a reminder. However, my own self is largely an effect of my actions and the world of interdependencies I shape through my actions. I feel supported just as I try to make other people feel supported. I own the good and the bad aspects of my life. That has taken another 20-odd years.

Yet in this life that has turned out not to be that different from the lives of my able-bodied peers, I had an immense fortune to avoid disablement through the labour market. The fact that wage labour is central to securing subsistence and welfare in our societies, and that ability plays a central regulatory role in the generalised system of competition in the labour market, makes the lives of disabled people truly abject. Across the EU roughly only half of the working-age disabled population is active in the labour market and only half of that population seeking employment gets a job. In semi-peripheral economies such as Croatia far less seek employment and only one-fifth of those get a job. Employers frequently prefer to pay a fine than to take a subsidy to accommodate a disabled worker. As a disabled worker, on average, you’re consigned to work in auxiliary jobs, in the informal economy or in the most exploitative conditions, subjecting yourself to abuse as your mobility in the labour market is extremely limited. Otherwise you become dependent, provided you have carers or institutions to depend on. What othering and bullying do in the early development, the limitations that you face in your adult life through the labour market and an inadequate care system make permanent. The sympathy that is extended to a kid is no longer there once you become adult and grow old.

To cut a long story short, two things that would make the lives of disabled people socially dignified: institutions have to transform how people who make them narrate and socialise differences from an early age on, and societies have to get rid of the labour market as a primary form of social integration altogether.